So, one of my resolutions for 2019 was that I wanted to blog more. It may seem late for new year resolutions, but if you are from Brazil, then you do know that the year only begins after carnival ends.

Today I will be reviewing some recent papers and a book on fringe communities. The papers are “On the Origins of Memes by Means of Fringe Web Communities” (best paper at IMC 2018 woot) and “The Web Centipede: Understanding How Web Communities Influence Each Other Through the Lens of Mainstream and Alternative News Sources”. The book goes by the provocative title of “Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4Chan And Tumblr To Trump And The Alt-Right”. While the book is very different from the papers, both analyze, in their way, these communities of the new age. These are sometimes determined by a website e.g., 4chan or /r/TheDonald, and other times determined by tribes, such as Incels, the alt-right, MGTOWs.

Now is the moment that I confess that, since I did my research for my paper on hate-speech (self-promotion one click away), I hate-watch a bunch of YouTube channels related to these communities. I won’t needlessly promote those channels here, but you may find (remarkably funny) commentary on them by watching Contra-points, Three-arrows or Shaun. I think my excitement to consume this kind of content comes from the often-moments where you think to yourself: “how can these people go so far?”, which, considering the number of documentaries about serial killers and cults, seems relatively common.

With this in mind, I bring you exhibit A: Roosh V, ex-pickup artist and overall cuckoo from the manosphere, which said in a impossible to watch 15 minutes video video and I quote:

I don’t think women should be educated beyond reading and writing. She only needs enough education to have children.

Given the absurdity of this quote (and I’ll assume throughout the post that these fringe communities usually talk outrageous stuff) the questions that arise are:

- How did we get here?

- What are the consequences of having such fringe communities?

- What does this means for the research community?

The book gives a lot of insight into (1) while the papers show alarming evidence related to (2). Last, I ponder about (3).

DISCLAIMER: Topics discussed in this article are somewhat controversial. In section 1, I (at least do my best to) represent Angela’s take on the issue. There was some controversy about the book (hit piece 1, hit piece 2, response 1). I have an opinion on many of these topics, and I try to make myself as clear as possible when stating my opinion by using italic. Section 3 is largely my own opinion, so I refrain from using it.

1. How did we get here?

How did we get from the “earnest hopeful days” where the interest of the average American was somewhat aligned with mainstream artists and media to the current disgust of anything mainstream by a large part of the population? Angela Nargle argues that some actors were involved:

- A weird group of internauts with a particular love for transgression.

- The rise of Tumblr-style PC-identity politics among a share of users and news pieces.

- Users that followed anti-semitic, race segregationist & mysoginistic ideologies.

Nargle’s thesis is that these three actors interacted to create what we currently have: The liberal lack of nuance (e.g. Ramen is Racist) created a breeding ground for online mockery, often in the form of memes or YouTube videos. In the book, Nagle uses Milo as an example for this, but in my opinion, there could be many other examples, like Dave Rubin or Thunderfoot.

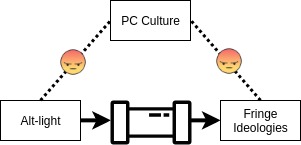

Amidst these memes and jokes, the real wolves eventually arrived in the form of openly white nationalist alt-righters, such as Richard Spencer. This approximation of the two groups, united by the hate of PC-culture, was what popularized fringe ideas. (for instance, the desire for a white-ethnostate where non-whites would “peacefully” leave)

A comment to be made here is that, while Nargle often uses the umbrella Alt-right, there are many other groups with fringe beliefs that joined this anti-PC movement and whose views shifted increasingly to the extreme right. Take Roosh V, for example. In 2001, he was a guy teaching other guys to pick up girls, a group of people named “pick up artists”, often with manipulative and “this just sounds wrong” procedures, but something very far from someone who says women should be educated only to be fit partners. The more you look into the internet, the more cases like this you find. Stefan Molyneux, for instance, which once held weird libertarian beliefs, has started to reproduce increasingly more alt-right-esque views. This transition is so common it even received a name: the libertarian-to-alt-right pipeline.

It is hard to get a complete view of this subject on a blog post, but the core idea I will get here is that these anti-establishment web communities and information sources (e.g., Breitbart) gained power in this culture wars against PC culture. This distanced public opinion from mainstream opinion. Meanwhile, fringe communities that already existed on the internet (for example, white nationalists) flourished in these spaces (or at least in their vicinities), creating real “radicalization pipelines.”

Why not make a diagram out of it?

Why not make a diagram out of it?

Last, it is worth remembering that this process is probably best seen as a “piece in a jigsaw,” as several other phenomena likely influenced the decline of the mainstream media and the radicalization of a large group of individuals. Things like the struggles of mainstream media to survive the online information era, the financial and health issues of a white rural America, and algorithms prioritizing content that receive a lot of engagement.

2. Consequences of fringe communities

Now we turn from “how did we get these fringe communities” to “these communities exist, so what are the consequences?” Before skipping to the academic papers, it is important to realize that two recent shootings can be traced back to these communities. The one in New Zealand was linked to a 70+ page manifesto full of white nationalist references and vocabulary widespread in the board. The least known, a school shooting in Suzano, a city in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil, was primarily influenced by Brazilian chans, such as 55chan and dogolachan.

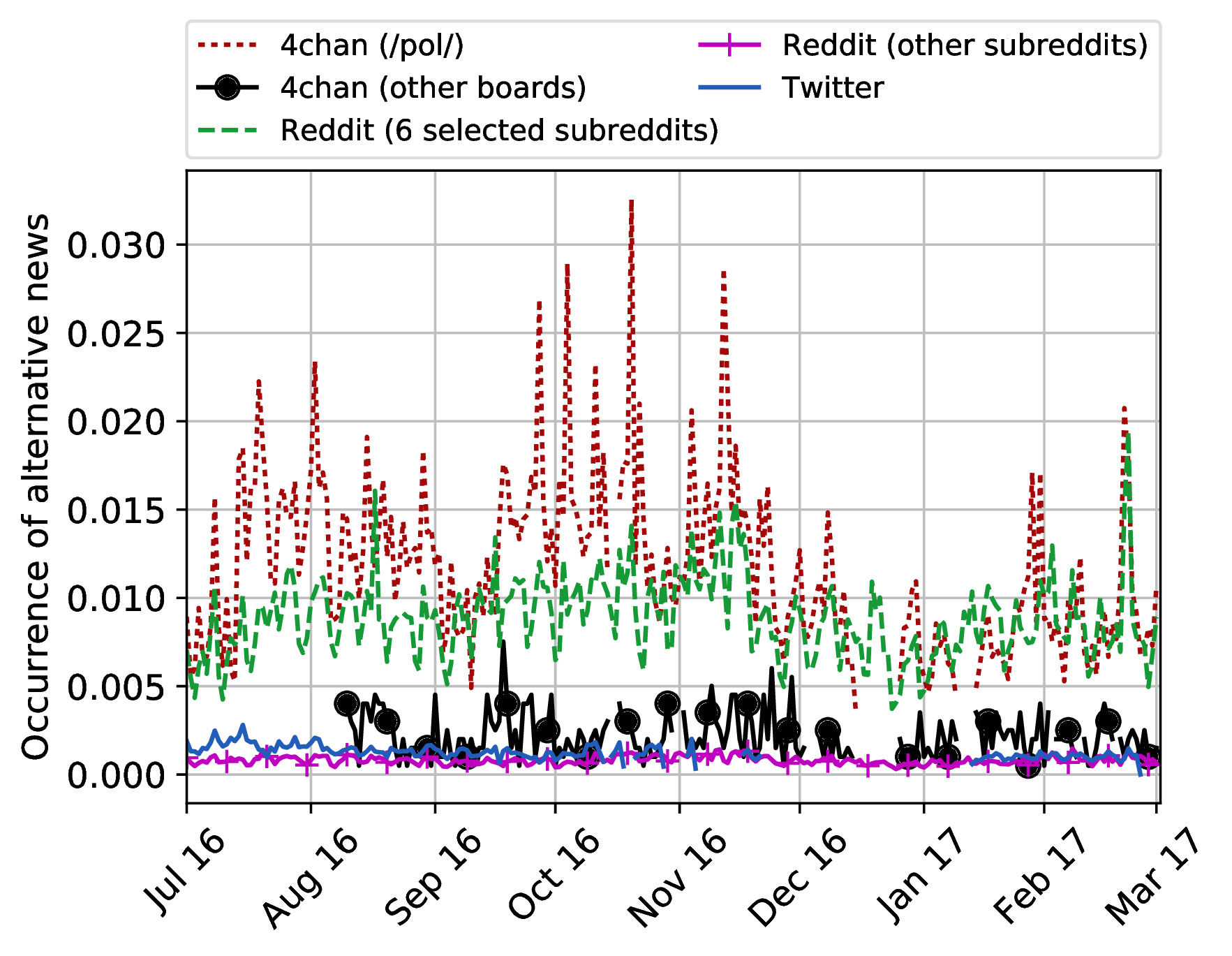

Knowing that these fringe communities can influence real life, let’s analyze two papers that measure their influence on the online discourse. The first, The Web Centipede: Understanding How Web Communities Influence Each Other Through the Lens of Mainstream and Alternative News Sources, attempts to measure how these communities spread alternative (and often fake) news into the information ecosystem. Researchers looked at four sources of information: Twitter, Reddit, 4chan, and news sites. Researchers classified news as alternative and mainstream and found that /pol/ and the selected subreddits exhibit a high percentage of “alternative” news.

Normalized daily occurrence of URLs for alternative news. Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

Normalized daily occurrence of URLs for alternative news. Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

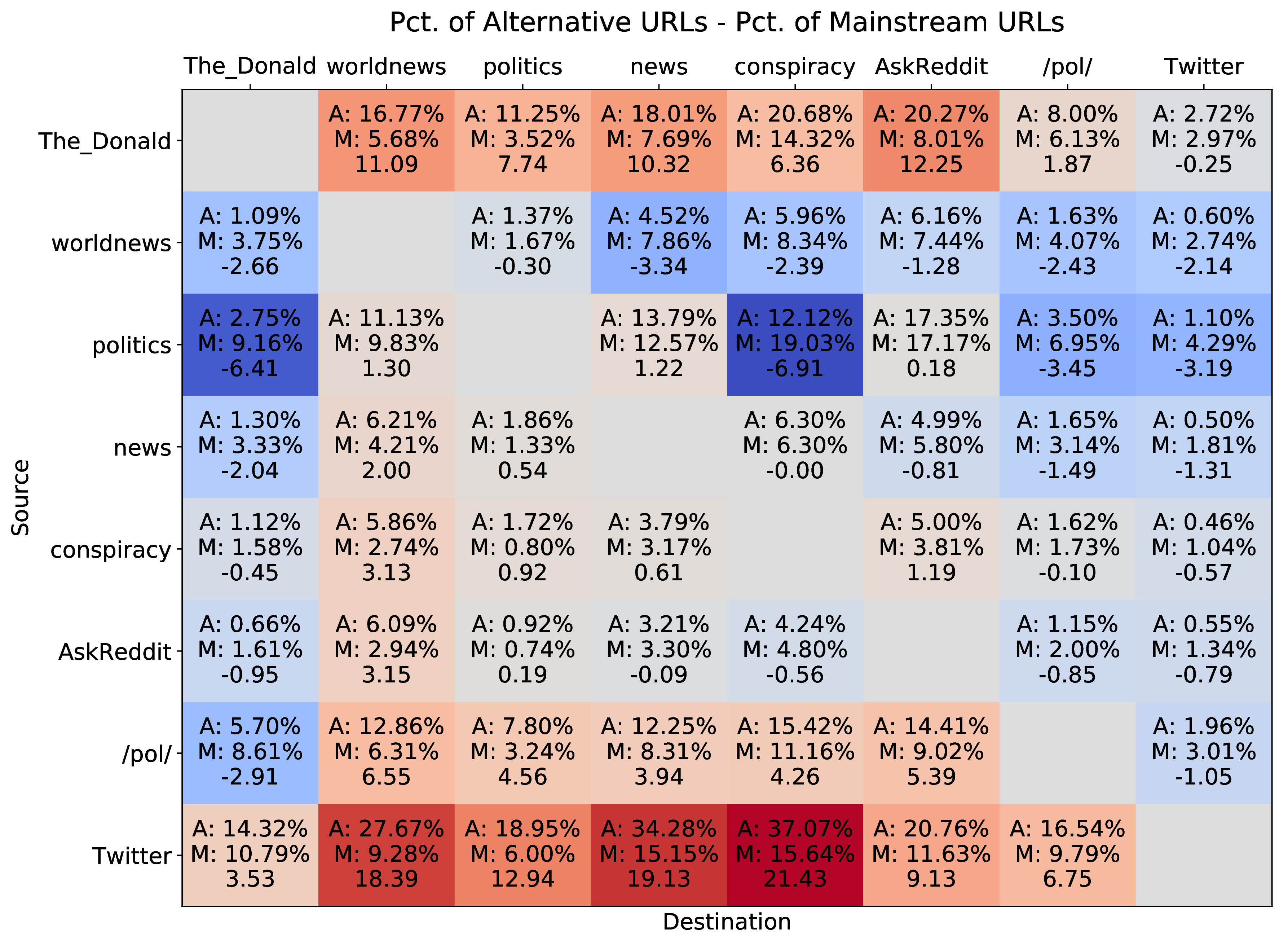

Yet, the authors go further and explore the question of who influences who? This can be studied by tracking where a news piece appeared first and using modeling techniques to quantify the influence of each community over another. Without getting into the gory details of Hawkes Processes, the authors find evidence that /r/TheDonald/ and /pol/ were responsible for around 6% of mainstream URLs posted to Twitter and 4.5% of alternative URLs published on Twitter. This is huge (pun intended), considering Twitter’s relative size. The complete influence matrix can be seen below:

Mean estimated percentage of alternative URL events

caused by alternative news URL events (A), mean estimated percentage of mainstream news URL events caused by mainstream news

URL events (M), and the difference between alternative and mainstream news (also indicated by the coloration). Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

Mean estimated percentage of alternative URL events

caused by alternative news URL events (A), mean estimated percentage of mainstream news URL events caused by mainstream news

URL events (M), and the difference between alternative and mainstream news (also indicated by the coloration). Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

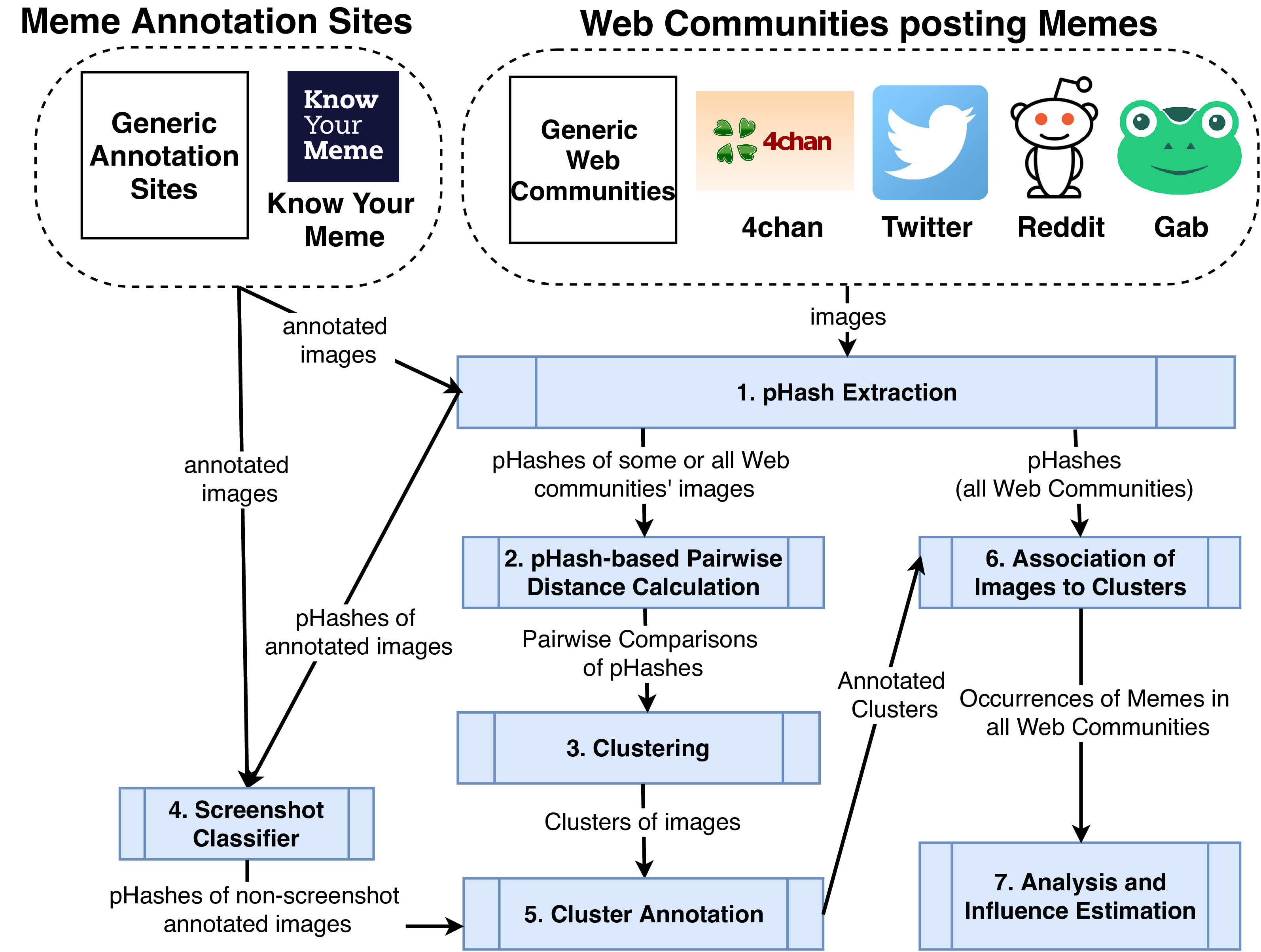

The second paper, On the Origins of Memes by Means of Fringe Web Communities (which has largely the same pool of authors), investigates a similar, yet in my opinion, trickier problem. While in the first paper, they consider the impact of these fringes communities in the news information environment, in the second, they consider the impact of these fringe communities in the meme information environment. This is more important than it seems, as memes played a big role in the 2016 election, and have been shown to radicalize even Facebook moderators. Another very cool thing about this paper is the framework they develop to process memes (for example, calculating the similarity between two images using p-hashing). The code is available here, and the pipeline is shown below.

High-level overview of their processing pipeline. Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

High-level overview of their processing pipeline. Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

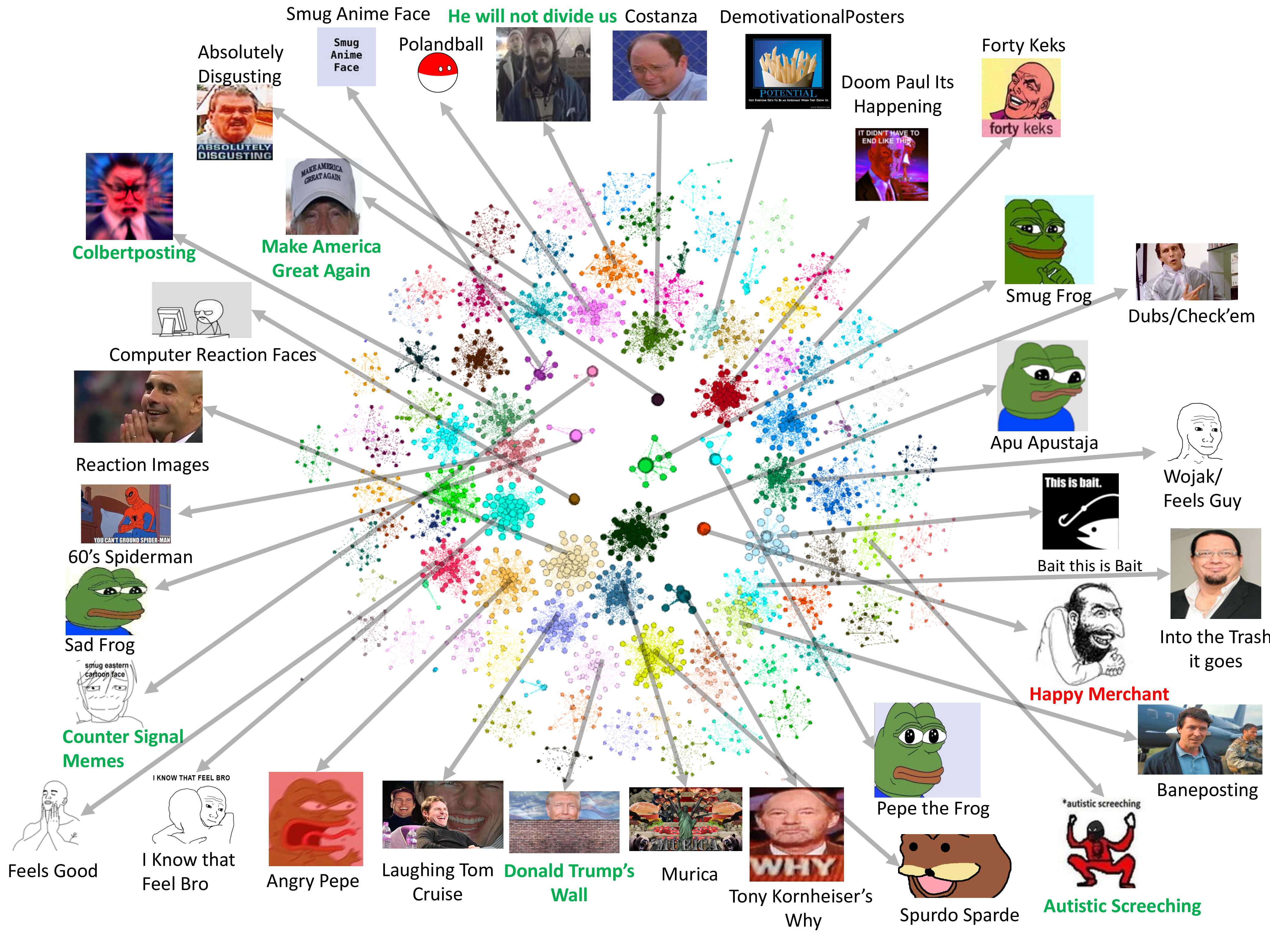

After collecting a bunch of memes from the (cool) Know Your Meme website, they use their pipeline to cluster memes (using pHashing and pairwise distance) and annotate them (as for example, racist/political). With this, and using data from web communities such as Reddit, 4chan, Twitter, and gab, they can get a good idea of the meme ecosystem of each of the different social networks. The meme clustering they did resulted in the beautiful image below.

Meme clustering at its finest. Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

Meme clustering at its finest. Image reproduced with permission from the authors.

Last, in a similar fashion to what they do in the previous paper, they use Hawkes Processes to model the inter-community influence in terms of memes. They find that /pol/, 4chans infamous “politically incorrect” imageboard is strong at disseminating racist memes across other communities (more than non-racist, which is an exception compared to other communities). But also that /pol/ is not very efficient, as hundreds of memes get created and posted there and never leave. Again, this resonates with the existing theory that /pol/ creates a “survival of the fittest” meme engineering environment.

3. What does this means for us as researchers?

The papers discussed suggest that fringe communities significantly impact the news and online memes. This is a big deal for anyone studying hate speech, polarization, and misinformation online. Two comments on that.

Adversarial Nature of Hate Speech and Fake News. The agendas in these fringe communities turn the moderation of hateful and fake content into adversarial problems. There have been some interesting approaches tangentially related to that (for example Magu’s paper trying to find code words for hate speech). Still, it seems to me that a more reasonable approach would try to create models that prevent this harmful content of “bleeding” from those fringe communities into the mainstream (YouTube and Twitter, for example). This would need (or at least I believe it would) constant monitoring of these fringe communities and continuous updates of hate/fake detection models (as well as moderation instructions).

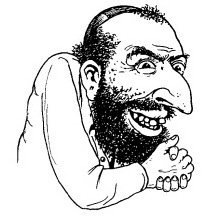

From KYM: “Happy Merchant is a cartoon portraying a male Jew based on anti-Semitic views, giving it characterizations such as greed, manipulative, and the need for world domination. Mainly posted on political image-boards such as 4chan’s /pol/ and 4chan’s /new/, it is used both ironically and seriously.”

From KYM: “Happy Merchant is a cartoon portraying a male Jew based on anti-Semitic views, giving it characterizations such as greed, manipulative, and the need for world domination. Mainly posted on political image-boards such as 4chan’s /pol/ and 4chan’s /new/, it is used both ironically and seriously.”

Context vs. Content. Content in social media is often racist or leads to fake/super-polarized narratives, but (and here is the catch) not to the average user. Memes are a great example of this. Take, for example, the happy merchant meme showed above, the 3rd most popular meme in /pol/. This simple image is used for hate speech against jews and supports the fringe belief of a secret jew circle that runs the world. Yet, many would argue it does not breach Twitter’s hate speech guidelines, as it is not hateful and fake by its Content, but hateful and fake by its context. This problem of Content vs. context has been captured, for example, by Davidson’s paper “Automated Hate Speech Detection and the Problem of Offensive Language”, where authors show that a huge problem for textual detection of hate speech is to distinguish between hateful and offensive speech (and also a motivation for my paper. I don’t think there is a silver bullet here. Still, again, I believe that these fringe communities may be an excellent place for researchers and policy-makers to grasp this “context” better and make better models and moderation instructions/pipelines.

Overall, my main takeaway is that research dealing with hate speech and fake news can be greatly enhanced by incorporating knowledge of these fringe communities, as they are often the source propagating fringe narratives and abusive behavior.