[This blogpost talks about our FAT* 2020 paper which you can read here]

This post is intended to address some of the comments and criticism w.r.t. my latest paper: Auditing Radicalization Pathways on YouTube. The paper got an unreasonable amount of attention, which involved media coverage, angry e-mails and upset YouTubers. Individuals associated with the communities in the paper were critical of aspects of the methodology. I believe most of these critics:

-

Misunderstood methodological aspects of the paper;

-

Don’t understand how doing research with large datasets work;

-

Criticize things that the paper does not say;

-

Largely ignored sections of the paper where methodological caveats were addressed.

Regardless, it seems plausible that my paper will play some role in shaping the debate around YouTube, and thus it is important to address some of the critics.

What The Paper Does Not Say

It is important to stress that the paper looked at two different directions:

-

Is there evidence for user migration from the I.D.W./Alt-lite to the Alt-right?

-

Is the recommender system responsible for this?

We find very strong evidence for (1), and don’t find strong evidence to answer (2). Overall, the paper says that migration from these communities did happen, but does not really answer why this happen. There are several reasons why this could be, such as: (i) the recommender system, (ii) something related to the demographics that these audiences target, (iii) something about the messages shared by the I.D.W./Alt-lite.

Wired’s piece, which I think was good and nuanced.

Wired’s piece, which I think was good and nuanced.

Secondly, the paper uses aggregated data, and thus it is tricky to say (insert member of the I.D.W. here) is radicalizing people. This phrasing assumes that we found a causal relationship between a specific type of content and radicalization, and is much stronger than the statement “individuals who commented on I.D.W. and Alt-lite channels consistently migrated towards Alt-right videos”.

Unfortunately, the way media covered the paper sometimes led to the junction of both of these things (like if one necessarily implied the other). The criticism to this jump in inference has been nicely capture by Kevin Munger and Joseph Phillips in their paper “A Supply and Demand Framework for YouTube Politics” (which I made another blogpost about), and subsequently by Wired’s article “Maybe it is not YouTube’s Algorithm that Radicalizes People”. Ironically, their own paper was hijacked by some media outlets as supposedly saying that individuals in the Intellectual Dark Web “de-radicalize” people, which they never claim.

Another thing that the paper does not say is that the recommender system IS NOT responsible. Given that we were unable to account for personalization and for how the recommender system work in previous times.

The Controls

A funny story here concerns the channels we called controls. People are very used to traditional controls in contexts such as randomized blind trials. Our study was observational, but with the advantage that we basically had all comments for the channels we are studying. In that sense, the control was a sanity check group, we choose a set of very large channels, to make sure the migration analysis was consistent. We went for media channels, but it could have been “sports” or “videogame”, or whatever. We actually debated quite a bit whether we should call this group “media” or “control”. A lot of the criticism was that the control group was a bunch of “leftist media outlets”, which really should not matter, for 2 reasons:

-

We wanted to get something not strictly related to the channels we were studying.

-

Even without this sanity check, many of the findings stand by themselves, because they bring ALL the information in the hundreds of channel studied. We don’t need to estimate, what is the increase in the likelihood of a user who commented in the Alt-lite commenting in the Alt-right, we have all such instances.

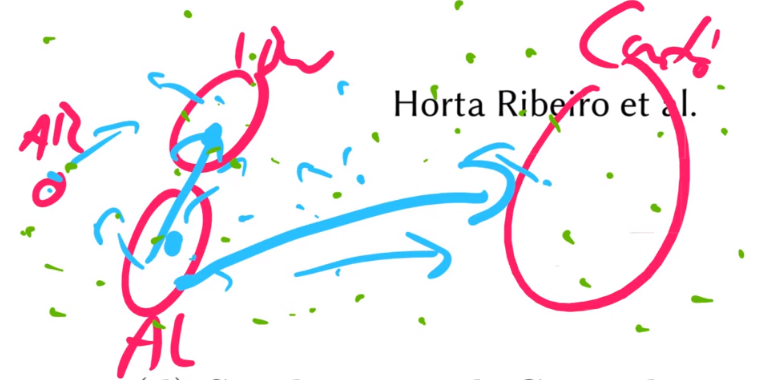

Another source of criticism which misunderstood something related to controls was a 45 minutes long video by Yannic Kilcher. He draws these 4 circles which are positioned in space and whose sizes represent the size of each of the 4 groups studied in the paper (see image below). He notices that the Alt-right is significantly smaller than the I.D.W. and the Alt-lite, and the control group is significantly bigger. He then goes on to propose the following model “imagine you comment at some YouTube video at random, the chance that it is an Alt-right video is extremely small, and then, you simply let people diffuse, and some will go on to the Alt-right”.

Screenshot from Yannic’s YouTube video

Screenshot from Yannic’s YouTube video

This hypothesis is largely disproved by the migration section of the study, particularly by Figure 4. If this (what Yannic says) was true, we would have a way larger number of people that first commented only on the Control group (for some given year), and then subsequently commented on the other communities (Alt-lite, I.D.W.) and eventually the Alt-right. In other words, if the high proportion of participants in the Alt-right being a consequence of random diffusion, we would also see that a high proportion of participants came from the control group, especially since the control group is so large. Yet, this interpretation requires that “the random diffusion process” happened in a way where 40ish percent of the folks that came to the Alt-right came from the smaller groups composed by the Alt-lite & I.D.W., and only 5ish percent came from the larger control group. What I find weird is that he actually goes on to comment these findings in Figure 4, but then goes back to the aforementioned argument, which doesn’t make sense.

Channel X does not Belong to Community Y

Another big source of criticism was that we mislabeled some of the channels in the dataset. This was in fact true for some instances (although it had small effect in the findings, as the significant mistake was done between Alt-lite and I.D.W., categories that were often collapsed in the main analysis). 2 or 3 mistakes will be rectified in the camera-ready version. But in other cases, what really happened is that certain content creators simply claimed “I am not in community X”. And here I feel it is really not up to them to do so, after all, we have to consider the adversarial case where these content creators do not want to make it explicit that they belong to one of the communities. We had a defined methodology and domain expertise, and that is it, it is not up to these people to create the taxonomies, but for researchers. That being said, taxonomies are of course imperfect, and this is particularly true if you have individuals that are as contrarian and anti-mainstream as the ones studied in the paper.

In this context, it is worth to stress that this is a large scale study and that mistakes in the labelling are prone to happen. In fact, I think we were quite transparent to provide a full list of channels in the main document of the paper (instead of throwing it under the desk in some supplementary material). We knew we would probably would piss someone with that, but still it felt like the fair and accountable thing to do.

On Qualitative Research

Lastly, another source of criticism was that we underestimated previous qualitative research done on the topic. On the abstract, it read:

Yet, the supporting evidence for this claim is mostly anecdotal, and there are no proper measurements of the influence of YouTube’s recommender system.

On the intro, it read:

Anecdotal examples of these journeys are plenty, including Roosh V ’s content creator trajectory, going from a Pick Up Artist to Alt-right supporter [24, 38], and Caleb Cain’s testimony of his YouTube-driven radicalization [37].

I agree we should be more careful with wording here, and the camera ready version will do better justice to it.