Yuri A. Santos (@santosyurial), Manoel Horta Ribeiro (@manoelribeiro), this text was originally published at Medium, and you can read it here.

What is the matter with Hate Speech and Online Social Networks?

The advent of Online Social Networks has profoundly transformed the way people communicate with each other in the contemporary world. Some of these platforms are very popular and aggregate millions of users that, daily, generate and publish a massive (and growing) amount of data, and even though much of the content produced every day consists of funny cat videos, some of it is not so cute. This would be the case of Hate Speech.

But why is it important to address this issue?

First, it is essential to consider that spreading Hate Speech is prohibited by law in many countries in which Online Social Networks operate. One interesting example would be Germany, which recently adopted rigid norms aiming to control the spread of Hate Speech, including the possibility of applying expressive fines to Social Media Companies.

Second, it’s known that Social Media usually profit from publicity and marketing and, most certainly, companies do not want their ads to be associated with Hate Speech, which could easily happen by mistake.

Third, due to the massive amount of content generated by users every day, it is desirable that the process of detecting (and deleting) Hate Speech is somewhat automated, with the aid of available modern techniques.

The purpose of this article is to introduce the challenges associated with the characterization and detection of this phenomenon, and to present some initial results our research group obtained in collaboration with researchers from Berkman Klein’s Center for Internet and Society.

Please be aware that this text contains racial slurs and foul language, so viewer discretion is advised.

But what is, precisely, Hate Speech and how do we find it?

One may believe that Hate Speech is a very easy and natural concept to understand and detect. In fact, some sentences targeting minority or vulnerable groups are very straight forward and, therefore, should be easily considered hateful by pretty much anyone with some common sense. For example, an user in an Online Social Network proclaiming “I hate Latinos” or “Latinas should die” will be considered hateful by practically any criteria, as in the United States people from Latin America are a minority that have historically suffered discrimination.

However, Hate Speech is not always obvious, which makes automatically detecting and characterizing it very challenging.

Initially, it is necessary to consider that the very conception of Hate Speech is quite loose and hardly agreed upon. For instance, even some very straightforward “I hate…” sentences are not considered Hate Speech by many if they are directed at groups of people in positions of power, such as men or white people. Some definitions only recognize Hate Speech if the target is a minority or vulnerable group.

Another problem arises because the text in Online Social Networks is noisy, often sarcastic, and associated with hyperlinks or images. On Twitter, for instance, a Tweet may seem hateful when analyzed in isolation but not when seen in the context of a larger conversation. Another good example here are racial slurs. While used negatively by outgroups, ingroups sometimes use them as terms of camaraderie or community.

These examples capture two aspects in which the detection and characterization of Hate Speech are more complicated than, for instance, the detection of spam or adult content (also desired in most social networks).

The first aspect of being considered is that Hate Speech relies heavily on context. This doesn’t mean that context hasn’t been used before in the detection of online misbehavior. It has. For example, the Internet Service Provider associated with an email is crucial to detecting whether it is spam or a legitimate message and has nothing to do with the message itself. However, with Hate Speech, the context on which a message is sent defines whether it is hateful or not.

The second is that there is no consensus on the definition of Hate Speech. Unlike traditional machine learning tasks like object recognition, on which human performance is considered optimal (or a proxy for optimal), people consistently disagree on what may be regarded as Hate Speech. Thus, algorithms must be trained considering high disagreement among human annotators.

Many of these findings stemmed from the Natural Language Processing (NLP) community, which has broadly discussed how hard it is to separate offensive speech from hate speech, the problems of annotating hate speech and the difficulties of analyzing code words used.

Given that the problem of automatically detecting and characterizing hateful content in Online Social Networks has to consider these two aspects, our group shifted the focus from the content itself to the users who spread it. We moved from “how to detect Hate Speech?” to “how to detect users that spread Hate Speech?”.

By adopting this approach, we believe it is possible to mitigate the problem of context during the automated detection process. In that sense, an account previously flagged as a possible Hate Speech “spreader” should be worth some attention by the moderation mechanisms.

How do we find hateful users?

Now that we decided to work on a different granularity than most previous work — dealing with users rather than content, we have a problem: how can we find these users? They are certainly not prevalent, and we still have the problem of defining hate speech. Our approach was the following:

-

We chose Twitter as the platform to conduct our research and Twitter’s own Hateful Conduct Policy as our source of a Hate Speech definition.

-

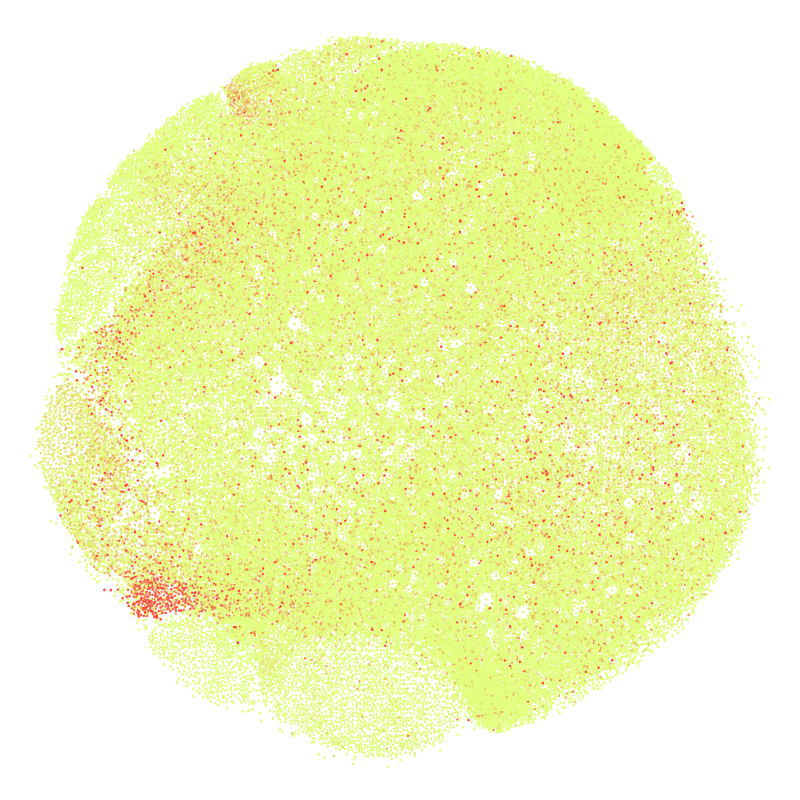

Then, we ran an algorithm to randomly collect data from 100,386 from English-speaking accounts, including their last 200 tweets, using Twitter’s API (Application Programming Interface). Notice that as some users have less than 200 tweets, so, in total, we have 19,536,788 tweets (approximately 194 tweets per person). We also collect the interactions between these accounts, keeping track of how they retweeted each other, as depicted in **Figure 1.

-

Initially, we identified accounts that used words or expressions that are very unlikely to be used in a context that does not characterize Hate Speech, like holohoax, racial treason, and white genocide. Such words and expressions were chosen from two widely recognized databases in the literature (Hatebase.org and ADL’s hate symbol database).

-

We collected the users nearby these hate-related words. The nearby part is crucial. We do not want to limit our sample only to accounts that specifically tweeted the chosen hateful words, as they are more likely to be labeled as Hate Speech spreaders. We needed a diverse sample because we didn’t want to be restricted to vocabulary that can be obviously characterized as hateful. Note: More technically, we find these nearby users by using something called a diffusion model, where we define a mathematical process through which users “influence” their neighborhood, so you become a bit more “nearby” to the users you retweeted, and if they happen to have used one of the words in our lexicon, you get up a bit of it for yourself. This is better explained in the original paper.

-

The final result was a sample of 4,972 users, alongside their 200 tweets. Notice that this actually represents approximately 964 thousand tweets! Which is quite a significant sample.

Figure 1. Network of 100,386 user accounts from Twitter. Shades of red depict the closeness of a user to others who employed words in our selected lexicon.

Then, we used Crowdflower, a service to crowdsource tasks to human annotators, to classify those users as “hateful” or “not hateful”. Each annotator was given a link to the web page of a Twitter user profile (selected among the 4,972) containing the 200 tweets collected. They were asked:

Does this account endorse content that is humiliating, derogatory, or insulting towards some group of individuals (gender, religion, race, nationality) or support narratives associated with hate groups (white genocide, holocaust denial, jewish conspiracy, racial superiority)?

They were also asked to consider the whole context of the webpage rather than only individual publications or isolated words. As a result, annotators classified 544 out of 4,972 users as hateful.

Some examples of tweets by users considered to be hateful include antisemitism, where the use of echoes is a reference to jews (notice that the phrases were slightly modified for anonymity):

Our (((enemies))) have used drugs, alcohol, porn, bad food and degenerate culture to enslave us. How do we win? Stop consuming their garbage.

Racism and racial segregation — often in the narrative of ethnostates, made “mainstream” by white supremacists like Richard Spencer:

I agree 100%. Stop the hate. Let’s separate. Each race can have its own ethnostates (whites, blacks, mestizos, etc)

A general hatred towards females — often blaming them for economic and political problems:

There Are 2.6 Million Ukrainian Refugees, how much do you want to bet those women with the ““welcome”” signs would protest them coming here?

An interesting detail is that several of the accounts annotators considered hateful had the following image of a cartooned frog — a variation of the infamous Pepe — as a profile picture. The pictures were often customized, including different clothes and facial hair — often alluding to some historical/political character.

Figure 2. “Groyper”, an illustration of Pepe the Frog present in several profiles considered hateful by annotators, often in some variation.

Among users that weren’t considered to be hateful by annotators, we highlight instances of anti-immigration stances:

The Danes must be pleased, it shall boost their commitment to diversity & multi-culturalism. Just like the Swedes next door: misguided.

And also foul language/offenses:

For real? Seriously? I am speechless! You will really? Dumb stupid bitch. (image of pro-immigration woman holding a banner)

Initial Findings

After isolating the final sample of 544 hateful accounts, we tried to characterize them in contrast with “normal” accounts. We wanted to see if there are any singularities when it comes to their network activity and language.

In addition, since we have the entire network, as depicted in Figure 1, we also look at the neighborhood of the users who were considered hateful — notice that, in practice, this means looking at users who retweeted hateful or normal users. The idea behind this is to understand the locality of the characteristics we analyze for hateful and normal users:

given a certain characteristic, are hateful and normal users inserted in neighborhoods of the network where this characteristic is prevalent?

As we will see soon, it is often the case. Additionally, due to homophily, we argue for the robustness of our results, as they are often observed not only in our limited (although significant) annotated sample, but also in the neighborhood of this sample, which is likely to share characteristics as birds of a feather flock together in social networks of all kinds.

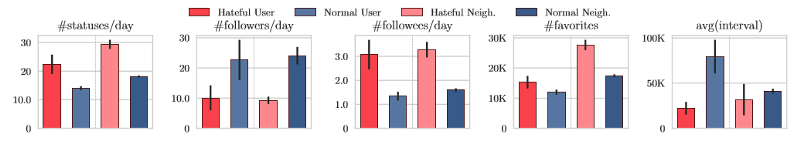

Figure 3. Average values for several activity-related statistics for hateful users, normal users, and users in the neighborhood of those. avg(interval) was calculated on the 200 tweets extracted for each user. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

We find that hateful users are power users, as depicted in Figure 3. They post more statuses per day, follow more people per day, favorite more tweets, and tweet in shorter intervals. However, they get, in average, significantly fewer followers each day. Notice that the same analysis holds if we compare their neighborhood in the graph (the users who retweeted the hateful users)! This suggests strong homophily, or in other words, that the users who retweet hateful users are pretty similar to hateful users themselves!

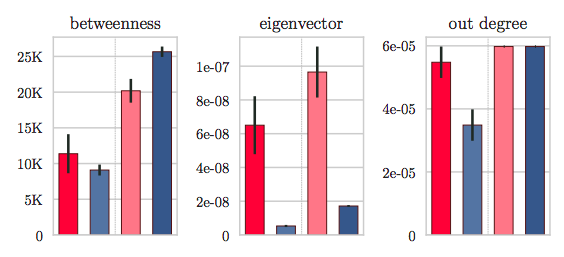

Figure 4. Median values for network centrality measures capture the importance a user account has in the network of tweets. Hateful users are not in the periphery of the network.

Furthermore, we want to analyze how important these users are! In Network Analysis, we have a set of metrics used for that purpose that we call “network centrality” metrics. They measure how important a node is in a network — using intuitions such as, is this node close to all other nodes in the network. When we analyzed such commonly-used network centrality measures, we found that the median hateful user and hateful neighbor are more central in the network than their counterparts. This is a quite counterintuitive finding, considering that hateful users are usually seen as “lone wolves” and anti-social people. This is depicted in Figure 4.

![]()

Figure 5. Lexical analysis results using EMPATH. Here, the idea is to see how prevalent words are in determined categories (work, love, shame, politics, etc) in tweets by hateful accounts, normal accounts, and their neighborhoods in the influence network.

Another intriguing finding came from the lexical comparison between tweets posted by hateful users and their neighborhood and those posted by normal users and their neighborhood. Our results suggest that the first ones use fewer words related to hate, anger, shame, terrorism, violence, and sadness, contradicting what common sense indicates about Hate Speech. Perhaps even more intriguingly, hateful users’ and their neighbor users’ tweets are more associated with the feeling of love than those of normal users, according to our lexical analysis. These results, presented in Figure 5, show how important it is to develop detection mechanisms that don’t rely solely on vocabulary. One hypothesis our group came up with for this is that the use of code-words and images play a strong role in the activity of these users.

What is next

Following on the idea that detecting hateful accounts is easier than classifying hateful content, we would like to develop mechanisms for the automated detection of Hate Speech in Online Social Networks based on this paradigm. Our future goal is to develop techniques that will help content moderator teams flag Hate Speech, in such a way as to assist them quickly in identifying and taking the necessary measures against hateful profiles. In that sense, we intend to develop human-machine collaboration-based techniques for detecting Hate Speech in different environments.

Another interesting direction is to work on the dimension of consensus. Most approaches to moderate hate speech are centered around regulatory entities (often the own Online Social Network). However, well-designed systems may use the wisdom-of-the-crowds (even polarized crowds) to curate the content in a decentralized and efficient fashion, as is the case with Wikipedia. Creating mechanisms that allow the community to moderate the content in Online Social Networks would be a significant step towards a better and safer web.

For more on hate speech check out our paper on arxiv. This work will be presented at the MIS2 workshop @ WSDM’2018. An updated version of this work was presented at ICWSM 2018