Recently Atila Iamarino (@oatila),a major science communicator in Brazil who is playing a very important role in the corona pandemic, marked me in a post by Sleeping Giants Brasil (@slpng_giants_pt). Sleeping giants is very cool initiative (inspired by the international version) that is trying to cut the problem of disinformation at the root, reducing the financial benefits of this type of “enterprise”. The question that was asked, abstracting the context a little, can be expressed as:

Could we measure the impact of disinformation on public health?

After giving my opinion at very late in that evening, I woke up thinking about it and decided to dwell on it a little more. I think this is a very nice example to discuss experimental studies (where researchers carefully design an intervention) and observational studies (with data that already exist), and also to talk about the limitations and difficulties of doing research mixing the real and the virtual world. As this post deals with a very serious subject, it is worth a disclaimer: I am not a doctor or an epidemiologist, I am a PhD student in computer science who works with social networks and observational studies. I know about causality and statistics but not about the medicine, virology, or public health. The only project I was ever involved involving health only served to make me realize how ignorant I am. What I’m writing here is more of a series of incomplete thoughts than a rigorous research direction.

The experimental route

In a hypothetical world, we could study the role disinformation with a controlled experiment. For example, we would choose participants completely at random, and for one half (the treatment group) of the participants we would send false news and for the other half (the control group), true news. Then we could measure, for each of the two populations, what was the coronavirus incidence rate, the number of deaths, etc. This approach is not possible because it poses a major ethical problem: we would be exposing a portion of the population to potential health risks.

Another possible approach would be to try to use interventions to reduce the impact of misinformation. In that case, instead of sending false news to candidates, we would send information that is reliable and which diminishes the harm false news to the treatment group, and nothing to a control group.

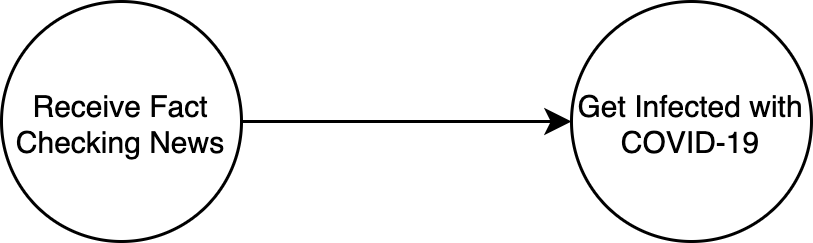

Suppose, for example, that we did the experiment described with a demographically diverse population, choosing at random who would go to the treatment group, and who would go to the control group. Suppose also that we have observed a lower incidence of COVID-19 in the treatment group. We can express our model with a causal graph:

Model 1: as simple as it can get!

Model 1: as simple as it can get!

However, this is not exactly what we wanted to study initially. I think this study would be interesting in itself, but let’s get back to the original question. We wanted to study the effect of disinformation, and that is not in this model! A model that would encompass this would be:

Model 2: notice that we want to study the mediator variable!

Model 2: notice that we want to study the mediator variable!

That is, the news countering “fake news” would change people’s susceptibility to misinformation, which in turn would increase the chance of an individual being infected with the coronavirus. We call this new variable a mediator variable.

In this context, our model is incomplete, as there are several things that influence both misinformation and the chance of someone contracting COVID-19. For example, age probably influences both the type of content you receive on Whatsapp/Facebook and your risk of getting the coronavirus. These variables are called cofounders. We are going to represent the existence of these variables as a dotted line between “deformation” and “coronavirus”:

Model 3: the dashed line represents confounders!

Model 3: the dashed line represents confounders!

In our scenario there is no co-factor between (fact-checks) and (misinformation), because our fact-checks are being sent at random! The exclamation is not accidental, because this graph structure we just saw is great for doing research! We can say that (fact-checks) is an instrument, and there are techniques to measure the influence of the variable (desinformation) on the variable (coronavirus) using this third variable.

However, the sad part of the story is that we would have to be able to first study the impact of fact-checks on the consumption of individuals’ misinformation. Honestly, I don’t know exactly how it could be done because this impact is extremely subjective. For example, we could collect all the links seen by each participant (which is already very unlikely to be achieved) and count how many fake news each person saw. In addition to the fact that this is extremely difficult to obtain for privacy reasons, and that the process would involve classifying hundreds of stories as true or false, it may be that, even with the fact-checks the person continues to receive misinformation, only that he does not believe in them anymore.

Moreover, it may be that the fact-checks may not help much! T his is not so absurd to consider, as there are studies that show that fact-checking may trigger the so-called backfire effect, where trying to correct false but rooted beliefs can end up reinforcing them [1] (note that there are other studies that have reproduced [2] and disputed this effect [3]). In this case, the fact-check variable would be what is called a weak instrument, and the study would be impaired…

Finally, it is worth mentioning that it is necessary to ethically consider whether this study is acceptable. After all, when doing this study, we are consciously deciding to give the fact-checks only to a fraction of the participants! For these difficulties, perhaps the observational framework would be more desirable, this is where we do not perform an intervention, but try to take data that already exists and to learn something from it.

Stick for the next post for more thoughts on that!