I’m steering my Ph.D. towards studying how things like moderation policies impact our information ecosystem, that is, the way people consume and produce content online (more on that later, I hope).

In any case, in EPFL we have to do a “candidacy exam” where the Ph.D. student has to discuss three papers broadly related to the research direction they want to pursue. As I did my literature review, a paper that stood out was “Hidden resilience and adaptive dynamics of the global online hate ecology”. Three reasons for that:

- It is AFAIK the only paper about content moderation ever published in the prestigious Nature journal. Although the topic has been widely explored in Computational Social Sciences/HCI venues;

- A quick skim of the paper suggested that they went as far as to propose content moderation policies;

- The paper deals with a topic I find tremendously important: fringe communities (as I wrote previously about). Their proposal is to consider the impact of moderation policies not only within a platform but across platforms.;

When I saw all of this I knew that I had to choose this paper, after all, this would be an important reference for my research. In what follows, I discuss a bit of the problem the paper tackles, the approach taken by the authors, and my thoughts about it. In short, the TL;DR; is that I find their approach problematic and do not think this is the kind of research that should be guiding moderation policies.

Many, many accesses…

Many, many accesses…

The Problem

The paper considers how moderation policies may impact fringe groups, but considers these groups not as atomic entities that exist in a single social network, but as distributed entities in a network-of-networks spread throughout the world on many different platforms (Facebook, VK, Telegram, etc).

The authors propose to examine how different intervention policies are effective in diminishing online hate in this distributed scenario. This question is particularly important because we know very little about the efficacy of moderation measurements outside of a single platform. For example, Chandrasekharan et al. have studied the efficacy of a series of Reddit bans in the subsequent behavior of users on Reddit. They found that in Reddit, users who were active in the banned subreddits became less toxic in subsequent Reddit posts (in other subreddits, evidently).

Yet, what happens when a subreddit gets banned and users migrate to other platforms?

Notice that this is not a “what-if”, but something that has happened a couple of times in the past. In the very event studied by Chandrasekharan, many of the subreddits (e.g. CoonTown or FatPeopleHate) migrated to voat.co, an alternative platform committed to lower moderation standards (to put it nicely, hahaha). In more recent years, the same happened with the infamous /r/Incels, which created their own standalone website Incels.co, as well as with the remarkably active /r/The_Donald subreddit, which after issues with Reddit moderation created thedonald.win.

In this context, there is clearly a trade-off happening:

- On one hand, as these fringe communities inhabit mainstream platforms, they are able to more easily recruit new members and may have more influence in the “mainstream” information ecosystem (for instance, things produced there may more easily reach other parts of Reddit). Therefore, banning these fringe communities seems like a good idea for the information ecosystem.

- On the other hand, as they inhabit the mainstream platforms these fringe communities have to “tone down” NOT to get banned, and thus, the very fact that these communities are in the mainstream puts constraints over them. When these communities migrate to alternative platforms, it could be that the lack of any moderation creates even more negative externalities to society.

Now that I have hopefully convinced you that this is an important problem, let’s move to the next obvious thing: what did the paper do?

The Solution

A nature paper is written for presentation, and not for analysis. So forgive me if I flip the paper upside down as I discuss it. But I will go for what seems to me to be the most logical route.

Their data and empirical observations

A considerable part of the paper consists of discussing their data: a bunch of hateful groups from VKontakte (a Russian social network) and Facebook. Their observations can be broadly grouped into three points.

-

First, they note that hateful groups have strategies that build bridges between otherwise independent platforms. For instance, there can be mirrored communities: groups that exist both in VKontakte and Facebook; and they can share links for communities in different platforms.

-

Second, they see that the network of hateful clusters across platforms connect individuals spread throughout the globe. This is particularly interesting as many of these communities are highly nationalistic, and dealing with issues related to their own countries (e.g. some hateful groups have very extreme instances against immigration, abortion, etc).

-

Third, they find evidence that these networks are “resilient” to adversities. Following a mass shooting with links to the KKK, they find rapid rewiring of KKK clusters, with new “bonds” being formed between existing clusters.

While these are interesting findings, I see many problems with their approach. My first set of complaints have to do with how little the authors describe and explore their data, using it only as a motivation. For example, I really wonder what is the prevalence of the so-called “bridges” between hate clusters? How did the authors determine the location of hateful clusters? How did the authors ascertain that the re-wiring that happened in the KKK clusters was really something uncommon for social media networks? What are the baselines? Unfortunately, I did not find answers for these in supplementary materials (which I hoped I would).

More broadly, however, I think that an even bigger issue here is that the representativeness of the data is never discussed. I wanted to check how the authors sampled the data and found the following statement in supplementary materials:

“Our data is not a sample (…). We collected information about clusters and kept moving to the next cluster until we returned to the same clusters. In this sense, our data is not a sample.”

Which is clearly wrong! Their data is a sample, they used a graph-based sampling approach which does not necessarily give them the full picture. Indeed, it could very well be that the “hateful communities network” is super fragmented and they only got one of its connected components.

Models, models, models

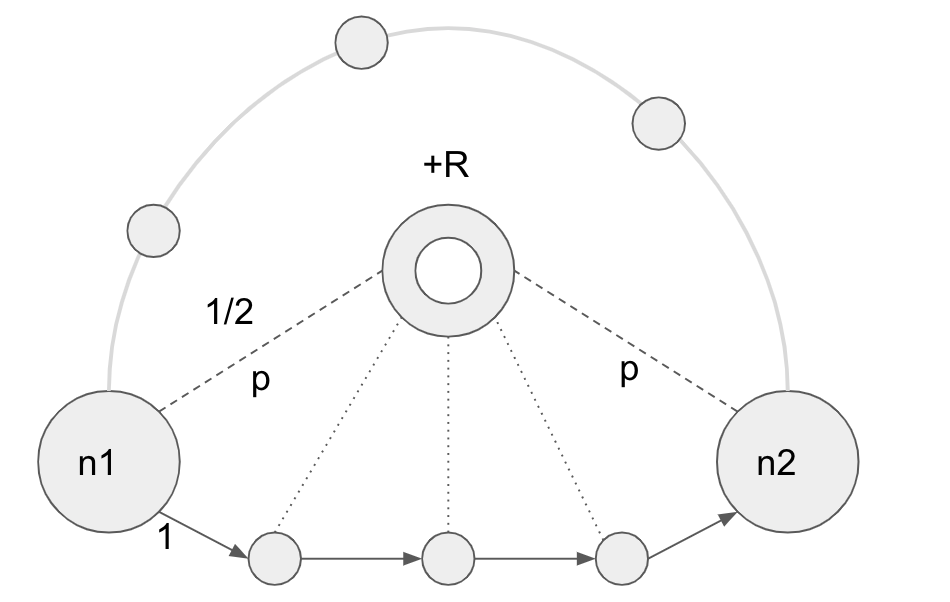

Besides describing this data, the paper main result is obtained through a toy ring-hub model. Which I illustrate and describe below:

Illustration of their model.

Illustration of their model.

- The model consists of a ring-hub network where hateful nodes in one platform are placed in a directed ring, where each node has a probability to be linked to another platform (by a bi-directional edge); This other platform is represented by the hub in the model.

- A parameter of the model is to which extent the social network A (in the ring) is connected to social network B (in the hub). This is determined by a constant p, which represents the chance that each node in the ring has to be connected to the hub.

- When content crosses platforms it incurs an additional cost R, which can be seen as a risk of content being moderated, or as a delay imposed by the work involved in changing platforms.

- They then proceed to calculate the average shortest path between hateful clusters in this model. They use this metric as a proxy for how effective hateful groups will be in spreading their message.

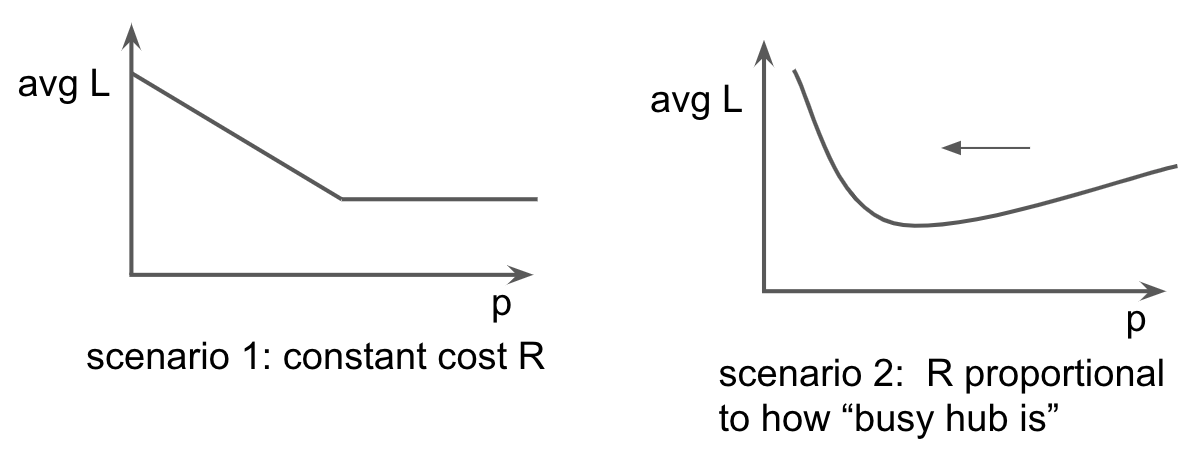

They then predict two possible for scenarios for this model:

-

Scenario 1: If the cost R is constant, then, for a given platform, moderating links is always good to “weaken” the global hate pathways. As we increase the number of links (p) the average shortest path decreases, up to a point where it is always worth taking the hub-path and then p does not matter anymore. So here, decreasing p is always good, so “blocking” hateful content from other platforms is always a good idea.

-

Scenario 2: Yet, it may be that this cost R is proportional to “how busy the hub is”. For example, if there is a lot of sharing between two platforms, the risk involved in content being moderated may be higher (is it?)! In this case, researchers found that reducing the number of links from one platform to another may actually decrease the average shortest path! This happens because as we increase P, we increase the cost R, but also we decrease the shortest path between some of the nodes. This conflict leads to a minima.

This illustrates the main finding of the paper. That moderation can have a backlash effect. It could be that moderating links actually make things worse! While this is interesting, I find that the paper does very little to address the obvious limitations here: this is a tremendously specific model, and researchers do very little to justify why it makes sense that:

- The communities are modeled as a ring, since this structure is so unusual in social networks;

- There is a cost R to cross social networks. For instance, for me, it makes more sense that the cost is when individuals spread content to bigger communities inside a social network.

- That this cost R is proportional to the number of links being shared across the two platforms. I don’t really think this is as obvious as it seems.

They use this main model to motivate a range of moderation measures, and they additionally justify each policy with an additional model (that has nothing to do with this ring-hub model). So for example, one of the moderation interventions they propose is to randomly ban users so as to keep hateful networks “under control”, but never completely destroy them. Other moderation interventions go way ahead and propose things that in my opinion are largely unjustified by this main model they propose. For example, they go as far as to propose to have a set of accounts to foster debate between dissenting hateful groups (think like paganists and Christian white supremacists).

Models are great when they are simple (and their assumptions very reasonable) and can explain a variety of phenomena. Yet, these are not the case for the models proposed. The main ring-hub model is far from “realistic”, and although it is a cool result, I think it is worth very little without empirical validation. The intervention-specific models are also questionable since the authors use a completely different model for each set of policies! You can surely find a model that presents some expected behavior that you want, but the big question is whether the model is appropriate.

How should policy-guiding research look like?

To sum up, the paper has limitations related to their data sample (and how much they explore it), and take modeling decisions that are questionable (as perhaps any model decision can be). Yet, I would like to zoom out a bit and really discuss why I think that this approach won’t work for guiding internet policy. When looking at other fields that deal with very complex systems like Medicine or Economics, we have a clear “ladder” that must be climbed for a research finding to bleed into practice. Modeling is often one of the first rungs of this ladder, and it makes sense since it motivates empirical inspection of a phenomenon. Yet, to suggest a drug or an economic policy with a simple model sounds inappropriate (even for someone like me who is only vaguely familiar with research in these areas).

If so, why should things be different for computational social science? Why should we run simulations on custom-made networks and assume that this is a good validation of a moderation policy? I firmly believe we should not. If anything, social networks can provide researchers with valuable data that allow for good empirical research (as it has), and I can’t see any reason why this should not be done as in economics: we need good observational studies, natural experiments, and (when possible) randomized control trials. It won’t be amidst the mess of social network data that model-driven policymaking will make a splash!